“Be lazy like a fox. Don’t keep reinventing the wheel. Take something that already works, copy, adapt, give credit and re-share. “

Author: Harish Sub

Open Source QOTD

It is easier to ship recipes than cakes and biscuits.

– Often attributed to John Maynard Keynes (but doubtful)

The Dutch Reach

The surrounding environment affects people to interact with an object differently. Take the simple car door. The dutch have a lot of cyclists, and most drivers frequently ride a cycle. So, it’s intuitive (to them) that a cyclist might be in your blind spot when you’re opening a door. So, using the far hand to open the door, allowing you to peek at the blind spot before opening the door, only seems natural.

This is the Dutch Reach .

Did you notice the other thing the driving instructor (in the video) said in passing? Holding the door with the left hand because it’s windy? Tells you a lot about the environment and how people interact with objects taking the environment into consideration.

Logo

Monochrome website logo: low-res

What we don’t know about… Telomeres

If you want to live longer, take good care of your telomeres– Washington Post, 13 January 2017

Molecular biologist Elizabeth Blackburn won the Nobel Prize in 2009 for the discovery of Telomerase, an enzyme made of protein and RNA subunits that elongates chromosomes by appending sequences of bases Adenine (A), Guanine (G), Cytosine (C), and Thymine (T).

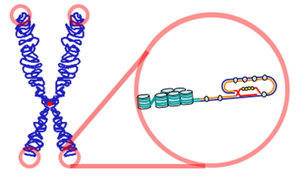

Now, a telomere is a DNA sequence at the tip of a chromosome. It’s commonly described as a sort of aglet, that little plastic sheath at the end of a shoelace. These ‘sheaths’, formed of repeating sequences of DNA that can be as long as 15000 base pairs, protect the chromosomes by preventing the base pairs at the end from unraveling. As cells age, these telomeres get shorter and shorter until eventually, new cells stop replacing old ones.

Telomere image courtesy commons.wikimedia.org

Telomere image courtesy commons.wikimedia.org

So telomerase, by elongating the telomeres, effectively slows down the shortening of telomeres as a result of natural ageing, and is fancied as a way to alter ageing at a cellular level. Telomerase is not usually active most somatic cells (cells of the body), but it’s active in germ cells (the cells that make sperm and eggs) and some adult stem cells.

Can telomeres really be lengthened?

In her book, The Telomere Effect: A Revolutionary Approach to Living Younger, Healthier, Longer, Elizabeth Blackburn suggests suggests that lifestyle choices are affect telomeres and consequently, how we age. But this view isn’t unanimous. While a variety of studies have shown that increased (moderate) activity, a mediterranean diet and getting sufficient sleep are linked to increased telomerase activity, all these studies are short-term studies and have been fairly limited in their scope and rigour.

Elizabeth’s co-author on the book, Elissa Epel, acknowledges that it’s unclear how specific lifestyle changes lengthen telomeres, and what effects this has on ageing in the long run. So far, only correlation has been shown rather than causation.

Contrary to its role in the robust propagation of regular cells, telomerase may also have a dark side. Cancer cells often have shortened telomeres, and telomerase is believed to suppress the shortening of the telomeres, thereby aiding the reproduction of these cells . If telomerase can be inhibited, this rapid division of the cancerous cells could be arrested.

So what don’t we know about telomeres?

A whole lot, to be honest. We aren’t sure there’s any causal link between telomere length and its effect on ageing. We also don’t know how exactly to regulate telomerase in cancer therapy. Just last month, scientists in Singapore announced that they may have discovered a protein ZBTB48 (the fourth known such protein after TRF1, TRF2, and HOT1) that regulates both telomeres and mitochondrial cells. There is still much to be understood about what goes on at the molecular level, and how effective the protein is in various cancers.

What We Don’t Know

There is a lot that we humans have learned. In a small fraction of the 4.5 billion years that the earth has been around, one species has progressed to astronomical levels of understanding, self-awareness, communication and discovery. In just the last five years, CRISPR as a gene-editing technology has started to look viable, the discovery of the Higgs-Boson has credence to the standard model, we have a fairly good idea of what happened as far back as 10-43 of a second, and AI has started to match human abilities in activities as complex as Go. On the face of it, we seem to have reached a state of diminishing returns. Are we in a state of scientific saturation?

“The more important fundamental laws and facts of physical science have all been discovered, and these are now so firmly established that the possibility of their ever being supplanted in consequence of new discoveries is exceedingly remote.” – Albert A. Michelson, 1894

Well, clearly not. Each generation’s conceit has led it to believe that there is nothing new to learn and that, surely, everything significant that needs to be known must be known by now. And every such generation has been wrong. Mysteries abound. Entire branches of knowledge are on the verge of being proven wrong. That is how science progresses.

It is at the very edge of our understanding that we learn, discover and progress. This is why it’s so hard to understand where we are going without understanding what we already know, and more importantly, what we don’t.