If you want to live longer, take good care of your telomeres– Washington Post, 13 January 2017

Molecular biologist Elizabeth Blackburn won the Nobel Prize in 2009 for the discovery of Telomerase, an enzyme made of protein and RNA subunits that elongates chromosomes by appending sequences of bases Adenine (A), Guanine (G), Cytosine (C), and Thymine (T).

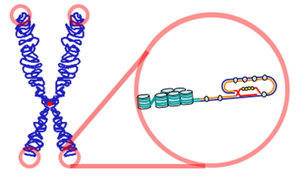

Now, a telomere is a DNA sequence at the tip of a chromosome. It’s commonly described as a sort of aglet, that little plastic sheath at the end of a shoelace. These ‘sheaths’, formed of repeating sequences of DNA that can be as long as 15000 base pairs, protect the chromosomes by preventing the base pairs at the end from unraveling. As cells age, these telomeres get shorter and shorter until eventually, new cells stop replacing old ones.

Telomere image courtesy commons.wikimedia.org

Telomere image courtesy commons.wikimedia.org

So telomerase, by elongating the telomeres, effectively slows down the shortening of telomeres as a result of natural ageing, and is fancied as a way to alter ageing at a cellular level. Telomerase is not usually active most somatic cells (cells of the body), but it’s active in germ cells (the cells that make sperm and eggs) and some adult stem cells.

Can telomeres really be lengthened?

In her book, The Telomere Effect: A Revolutionary Approach to Living Younger, Healthier, Longer, Elizabeth Blackburn suggests suggests that lifestyle choices are affect telomeres and consequently, how we age. But this view isn’t unanimous. While a variety of studies have shown that increased (moderate) activity, a mediterranean diet and getting sufficient sleep are linked to increased telomerase activity, all these studies are short-term studies and have been fairly limited in their scope and rigour.

Elizabeth’s co-author on the book, Elissa Epel, acknowledges that it’s unclear how specific lifestyle changes lengthen telomeres, and what effects this has on ageing in the long run. So far, only correlation has been shown rather than causation.

Contrary to its role in the robust propagation of regular cells, telomerase may also have a dark side. Cancer cells often have shortened telomeres, and telomerase is believed to suppress the shortening of the telomeres, thereby aiding the reproduction of these cells . If telomerase can be inhibited, this rapid division of the cancerous cells could be arrested.

So what don’t we know about telomeres?

A whole lot, to be honest. We aren’t sure there’s any causal link between telomere length and its effect on ageing. We also don’t know how exactly to regulate telomerase in cancer therapy. Just last month, scientists in Singapore announced that they may have discovered a protein ZBTB48 (the fourth known such protein after TRF1, TRF2, and HOT1) that regulates both telomeres and mitochondrial cells. There is still much to be understood about what goes on at the molecular level, and how effective the protein is in various cancers.